Marathon Baby

Feb 26, 2020 Amy Paturel, Photos by Ted Catanzaro Original Article – Here

Fueled by the power of knowledge and unparalleled access to supportive resources, Matt and Marci Tatham take their young son’s genetic disorder in stride.

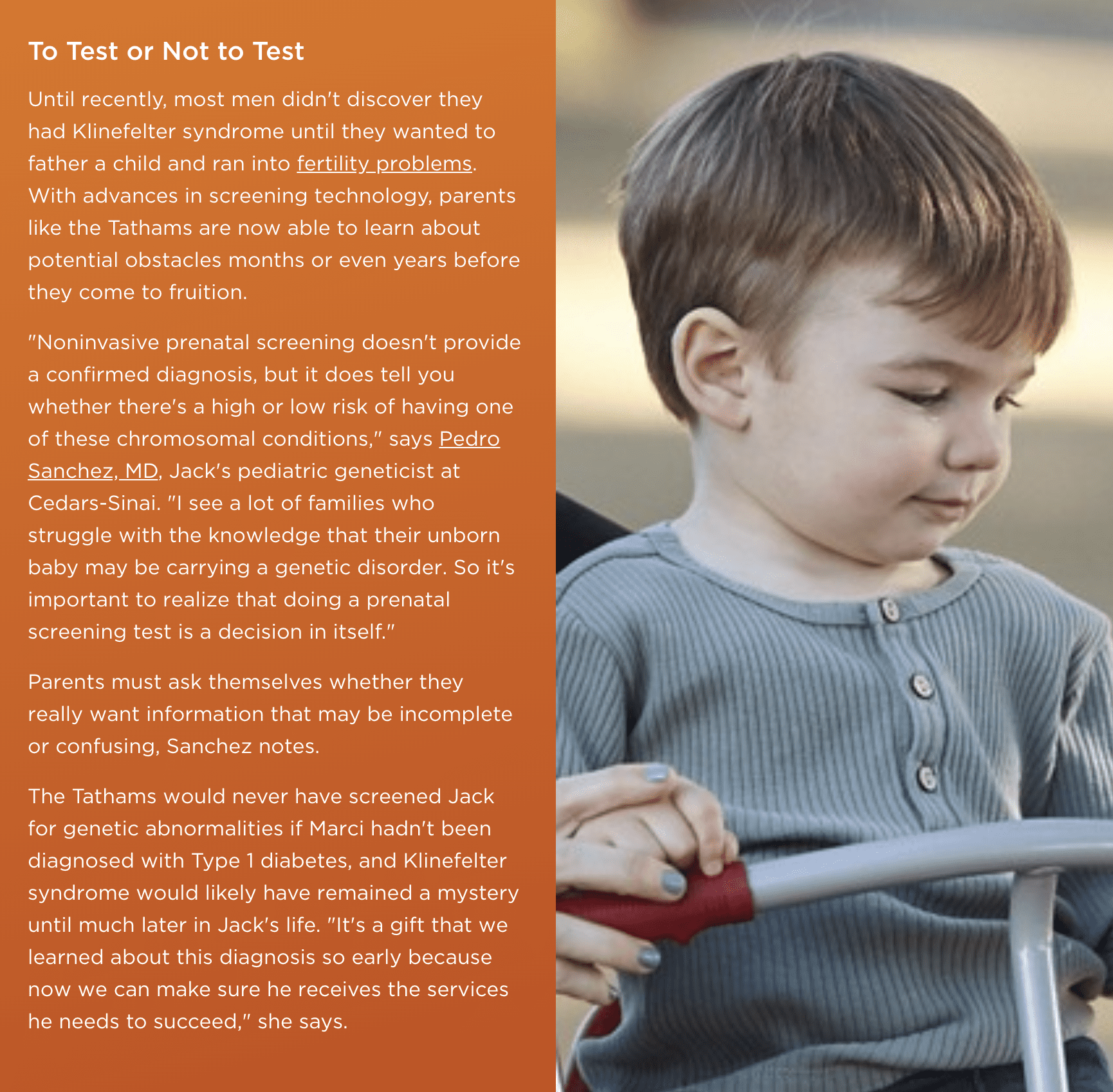

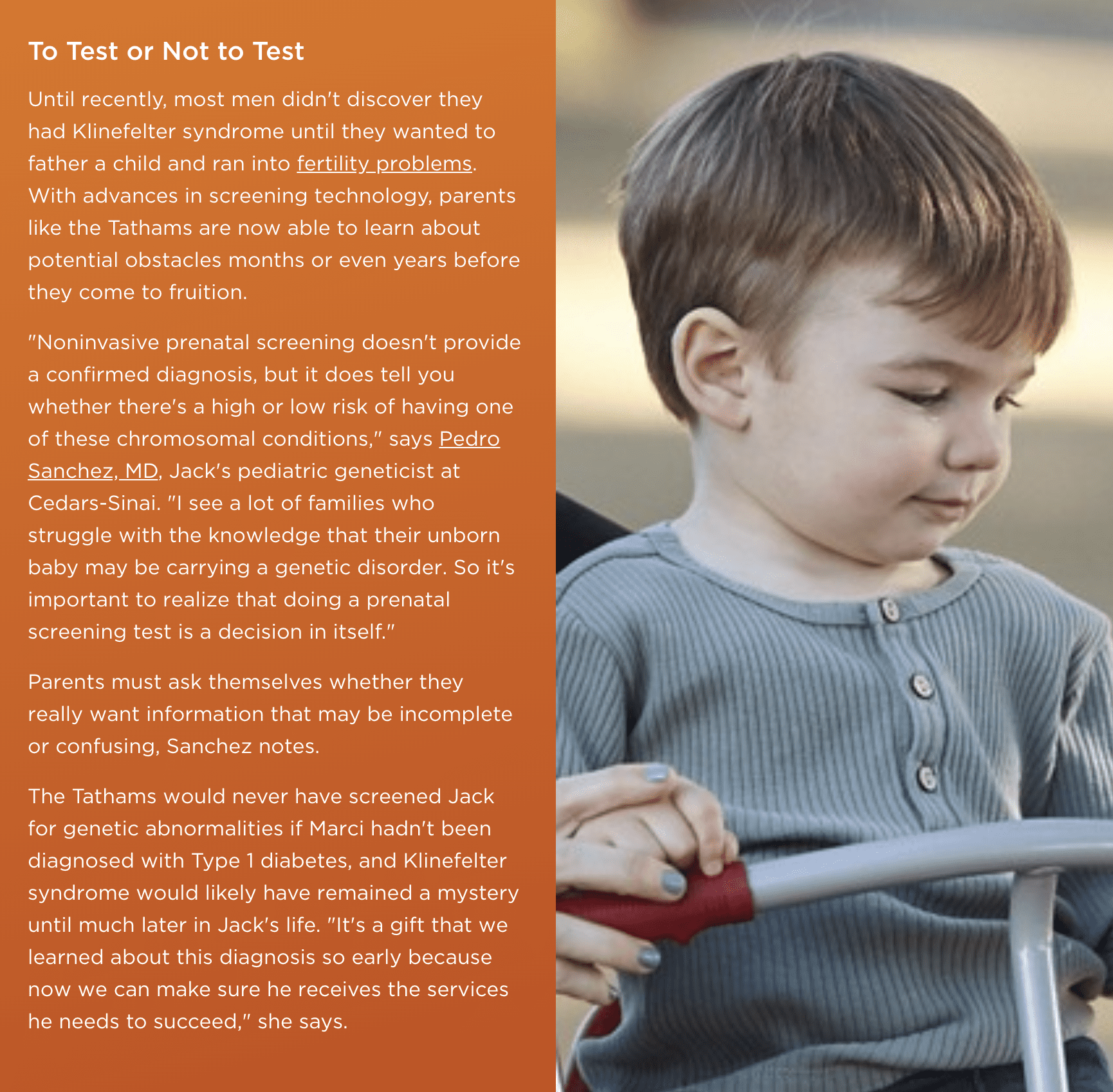

On any given day, Marci and Matt Tatham follow their giggling, nearly 2-year-old son, Jack, through their cozy Playa Vista apartment. The space is custom designed to cater to Jack’s curiosity and sensory development. A space shuttle fort allows for easy games of peekaboo. Toy airplanes and helicopters hover near the ceiling, and a playhouse on the patio opens the door to Jack’s imagination.

Engaging Jack’s senses during playtime helps keep his development on track. Though nothing in the toddler’s chipper demeanor indicates it, he has a rare syndrome that can lead to developmental delays in the short term and more serious outcomes later.

Marci Tatham learned she was pregnant just two weeks before running the New York City Marathon in 2017. Diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 2012, she was determined to join her fellow Type 1 teammates. “It never occurred to me not to run, but because I was pregnant, I decided to trot rather than run at full speed,” she says. “I realize now that running that race somewhat represents Jack’s life and how it’s beginning to take shape.”

Even though Tatham was only 26 at the time, diabetes put her pregnancy into a high-risk category. So when she was about 10 weeks along, her Cedars-Sinai obstetrician encouraged her to undergo a noninvasive prenatal screening for genetic abnormalities in her baby.

“The genetic counselor told me I tested positive for a chromosomal abnormality that’s only present in males,” Tatham recalls. “That’s how I found out we were having a boy.”

She froze, paralyzed with fear, confusion, anger, sadness and denial. There was a 33% chance her son would be born with Klinefelter syndrome, a disorder that affects about 1 in 650 newborn boys. Klinefelter syndrome occurs when boys are born with an extra X chromosome, in addition to the usual XY that identifies males.

The presence of an extra X chromosome may result in underdeveloped testes, testosterone insufficiency, and delayed or incomplete puberty—and it almost universally results in low sperm count. Affected boys can experience speech delays, decreased muscle tone and social-emotional deficits. The syndrome is also associated with mental health disorders, autoimmune conditions, metabolic syndromes and certain types of cancer.

“My mind was reeling,” Tatham says. “If Jack has Klinefelter syndrome, what will that look like for him? Will he be ‘normal’? Will he excel in school? Will he be able to have children?”

But it’s not in the Tathams’ DNA to get bogged down with negative possibilities. Fortunately, Matt Tatham was able to draw on his career skills and training. As manager of demand planning for The Honest Company, his mind is primed to forecast and strategize. The pair hit the ground running, poring over research papers, scouring the internet for parent support groups and spending hundreds of hours online learning about Klinefelter syndrome.

The couple also found a “coach”—Karina Eastman, MD, a pediatrician at Cedars-Sinai—to help them navigate the rocky terrain after Jack tested positive for Klinefelter shortly after his birth.

Charting a New Course

When the Tathams brought baby Jack home, they were looking forward to spending time together as a party of three, taking him to the park, visiting the beach, and hanging out with friends and family. But those dreams had to be balanced with a rigorous treatment schedule.

“Dr. Eastman was instrumental in partnering with us to select the best services for Jack’s needs,” Marci Tatham says. “Unlike many pediatricians, she understood Jack’s diagnosis and gave us clear direction for next steps. With her guidance, we have been able to give Jack not only an active childhood but also the best healthcare.”

Doctors like Eastman face the challenge of explaining a syndrome that falls on a spectrum. Klinefelter syndrome’s effects range so widely that some males are severely affected while others don’t even realize they have the condition. Only 25% will ever be diagnosed.

“It’s hard to say from birth how Klinefelter syndrome will affect a child because it varies so much,” Eastman says. “But the Tathams have done a lot of research and they are very proactive with Jack. He’s on track for his age, and I credit that to early intervention.”

By the time Jack was 1 month old, he had a team of Cedars-Sinai specialists ensuring he received the best care, including a geneticist and a pediatric endocrinologist. At 2 months, Jack started occupational therapy and physical therapy sessions to help build his motor skills and at 1 year he began speech therapy—all three of these services are less than 10 minutes from the Tathams’ home.

Jack’s mom doesn’t sit on the sidelines during these sessions. She’s an active participant, learning tools that will encourage her son’s development. “I take what I learn during his therapy sessions and weave it into his playtime at home,” she says. All of this work is helping Jack master climbing and balance and explore different foods, textures and sensory input—activities that can be challenging for boys with Klinefelter syndrome. He’s also learning how to ask for what he wants.

By the time Jack was 1 month old, he had a team of Cedars-Sinai specialists ensuring he received the best care, including a geneticist and a pediatric endocrinologist. At 2 months, Jack started occupational therapy and physical therapy sessions to help build his motor skills and at 1 year he began speech therapy—all three of these services are less than 10 minutes from the Tathams’ home.

Jack’s mom doesn’t sit on the sidelines during these sessions. She’s an active participant, learning tools that will encourage her son’s development. “I take what I learn during his therapy sessions and weave it into his playtime at home,” she says. All of this work is helping Jack master climbing and balance and explore different foods, textures and sensory input—activities that can be challenging for boys with Klinefelter syndrome. He’s also learning how to ask for what he wants.

“Jack is the first patient with Klinefelter syndrome that I have followed from birth,” Eastman says. “My job is to make sure he sees the right specialists and that he’s getting the services he needs so he stays on track with his development.”

It’s a busy schedule, to be sure, but Jack has met every milestone and, even though he’s still very young, the family is learning more every day about how he will grow, think, learn and develop.

“Living with Type 1 diabetes has prepared me to embrace Jack’s syndrome and teach him how to persevere through his own unique challenges,” Marci Tatham says.

It’s too soon to tell how Klinefelter will affect Jack down the line. That uncertainty can be unnerving for his parents. “It’s a one-day-at-a-time kind of thing,” says his mom, whose optimism and determination continue to grow alongside her son.

“As Jack’s life unfolds, we will begin to see how this will impact his development, learning, social skills, and long-term health and wellbeing,” she says. “In the meantime, we’re learning to let him run this race on his own timing.”

“The idea is to see if keeping testosterone levels in the ‘normal’ range can improve outcomes for these kids,” says B. Michelle Schweiger, DO, MPH, who is Jack’s pediatric endocrinologist.

Cedars-Sinai offers comprehensive pediatric endocrinology services for children and young adults with diabetes and endocrine disorders, from newborns up to age 21.

Learn more about Pediatric Endocrinology and other specialty services at the children’s health center at Cedars Sinai.

One Response

My 8 months old baby boy has xxy and testerone shot 3.4.5. Months. İs 6 month-1 years New? Sorry for my english.