Klinefelter syndrome/XXY transcends the labels and limitations often imposed by old studies and misinformed narratives. First identified in 1942, Klinefelter syndrome has been the focus of relatively few research studies to help better understand the diagnosis.

Around 1 in 500 males are born with this syndrome, but only 35% will receive a diagnosis in their lifetime. This means around 65% of men with XXY will live, never knowing they have it. With increased awareness, changes in prenatal genetic testing, and increased access to fertility options, increased and earlier diagnosis is becoming more common.

Physical signs and symptoms can vary greatly, as XXY presents itself along a spectrum. Some common physical traits can include small testicles (often resembling the size of pistachios), tall stature, less facial/body hair, less muscle bulk, and more fat around the middle. XXY is frequently associated with low testosterone levels which may lead to delayed puberty, chronic fatigue, cognitive fog, diminished motivation, and decreased libido. Most XXY men are infertile, yet numerous have overcome this obstacle to build families through alternative means such as donor sperm with IUI or IVF, adoption, and micro-tese surgery.

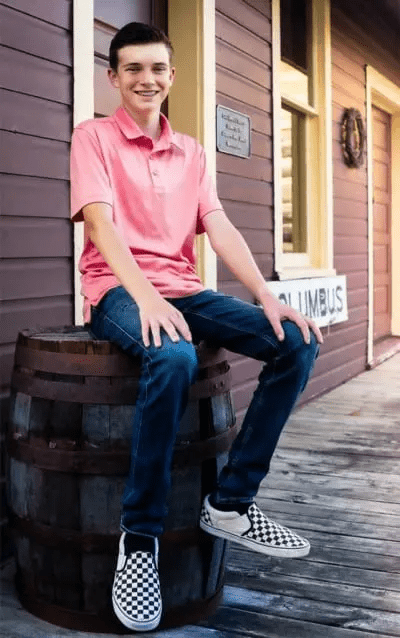

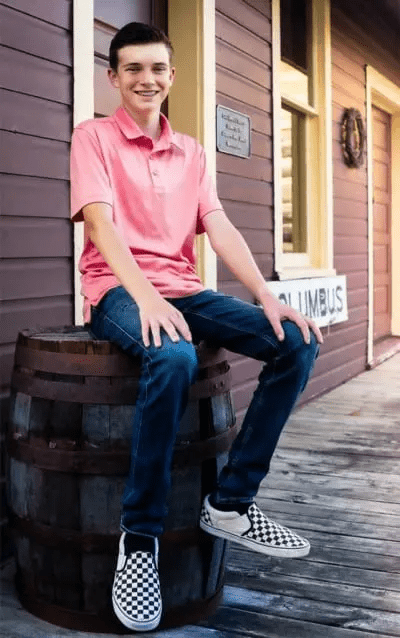

Despite the negative portrayals often found online or in old studies, a Klinefelter/XXY diagnosis does not extinguish the possibilities of a bright future. Among our community, positive traits abound, including kindness, empathy, creativity, hard work, and hands-on and visual learning. By focusing on the whole experience of those with XXY, we are changing the perceptions, increasing community support, and empowering our community to thrive.

Klinefelter syndrome affects about 1 in 650 newborns who were assigned male at birth. It is the most common sex chromosome disorder, which is a group of conditions caused by changes in the number of sex chromosomes (the X chromosome and the Y chromosome). Klinefelter syndrome is not inherited; the addition of an extra X chromosome occurs during the formation of reproductive cells (eggs or sperm) in one of an affected person’s parents.”